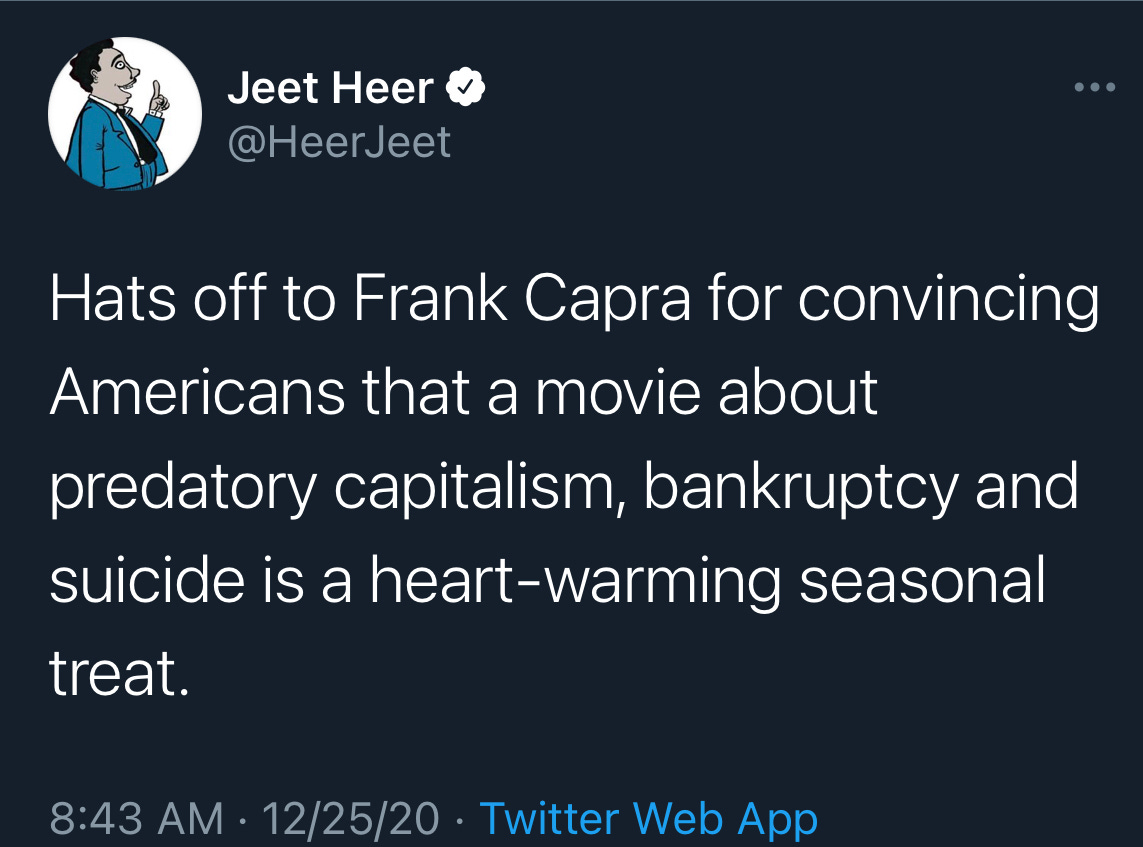

Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life gets viewed – and dissected – countless times this time of year. Plenty of takes are to be had, although the cynical or glib ones like this truly grate:

(I know I should consider the author of the tweet, but still.)

For starters, that’s not what Frank Capra was doing. It’s a Wonderful Life is a Christmas movie just like many now claim Die Hard is a Christmas movie – part of it happens to take place during the Christmas season. But its Christmas finale does feels special considering the themes of the holiday – goodwill toward others, giving to those you love and to those in need, etc. And for Christians, the story of the birth of a savior and a source of redemption.

That last part relates to what I’d wish we talked more about when it comes to the film. Namely, that George Bailey suffers from depression.

It’s not explicitly stated in the movie – I don’t imagine they talked much about mental health in 1946, when the film was released, certainly not like we do now. Hell, we didn’t talk about it 10 years ago like we do now. But George, played by Jimmy Stewart, certainly struggles throughout the film, and as the main character is often seen as the one from whom we should learn our main lesson – that life has value, even when you don’t achieve the type of success you had once envisioned for yourself, and there is beauty to be found in the collective. (The lessons of anti-capitalism and corporate greed resonate as well, but I only have so much time.)

But George isn’t who we should emulate, at least not beyond taking to heart the restoration, if not creation, of his belief in his self-worth. We are already George, and we all struggle with this notion. The real hero of It’s a Wonderful Life and the person who deserves our praise? Mary.

A quick note on the name Mary: I find that most characters with such a name (or the variant Maria) are good, even Good. It’s hard not to think of the biblical Marys, beginning with the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ. The New Testament is filled with Marys (seriously, there are a bunch) who had a role in Jesus’s life, from Mary, the sister of Martha, who sat at his feet to listen to him, to Mary Magdalene, who was both at his crucifixion alongside his mother and Mary, mother of James – the latter two being among the women who saw his empty tomb and went to tell the Apostles. They and many other women spent time around Jesus, who respected them, and were the first to believe in and spread the news of his resurrection. (In many ways, the Bible doesn’t have a woman problem; man, who has been in charge of interpreting it for so long, does.) Often, the Marys of literature and screen are a sort of amalgamation of those faithful Marys.

Life’s Mary (Donna Reed) is just as fervent a believer, and her belief is in George. She loves him, knows him, trusts him. She is the first to join his side and do the right thing even if it’s the hard thing, such as giving away money saved for their honeymoon to keep the old Building and Loan afloat. George is the one who tends to gripe about his lot in life – seeing his peers move past him in status and move away from their hometown – and we’ve all been there at some point. How easy it is to look up old friends on Instagram and believe through the carefully staged photos that their lives just might be better than ours.

Mary is far more secure in herself and in her family. So when George finally starts having full depressive, perhaps manic, episodes – trigged by Uncle Billy misplacing the Building and Loan’s money and not knowing the evil Potter has it – she knows what to do.

Watch this crucial scene – both how George is acting, and how Mary reacts.

She almost says something she’ll regret, but she stops herself. Her concern is for George, and the children. Again, she knows him. So watching him like this – spiraling, ranting, lashing out, being annoyed at the littlest of things – she knows something is wrong. The easiest thing in the world would be for her to lash out, too. To fight back. That’s what a lot of us would do, and often do in our own relationships. But she doesn’t. He leaves, and she immediately gets to work.

Mary’s continued goodness happens offscreen while George learns his lesson – a sort of backward A Christmas Carol via the angel Clarence – that his life had made a difference and has inherent value. Think of this like very fast and mind-bending therapy. In the real world it usually takes people longer to come to George’s conclusion, and even so we don’t all reach his joy-filled state of running through his town, now back to its familiar look as opposed to the version that would have come to pass if he’d never lived. But George gets to fast-forward through the sessions and medications, and runs home see the woman he loves.

For my money, she has an even bigger gift in store than what Clarence helped him see. No, not the money the good people of Bedford Falls and beyond deliver once Mary raises the alarm that George is in trouble. It was the act of recognizing his trouble, looking past his behavior, and giving him another chance that is what’s remarkable. In short, she shows him grace.

In my middle school days, my father once taught a Wednesday night Bible class at church for my grade. Each week he would take a word from the Bible – the Fruits of the Spirit, generally, and some others, and break them down for us. What did they actually mean? I’ve always remembered the shorthand he taught us to tell the difference between mercy and grace. Mercy is not receiving what you do deserve. Grace is receiving what you do not deserve.

The kind of grace George receives is transformative. I should know.

I have been depressed for half of my life, but only clinically diagnosed as such for two years. I struggled in many ways in grade school with self-worth, and once my best friend, Katie, died in a car accident when we were 16, my slow, slow spiraling began.

My lashing out really geared up in college, culminating around my senior year with me showing up at a professor’s house, inconsolable and in tears. He didn’t know what to do, so he calmed me down and sent me on my way. I needed counseling, but it just wasn’t in his or my or my parents’ vocabulary. I’m a high-functioning depressive, so my symptoms often hide themselves from those unfamiliar with mental health; they only see the projects I’m involved in and not how I’m using them to distract myself from confronting my actual problems.

About a year after graduation, a primary care doctor put me on an SSRI, which I took for a decade. Various ups and downs ensued at my subsequent jobs. (God bless the patient bosses that were put in my life and never fired me.) In 2015, a good friend of mine, Jeff, died of cancer as a complication of AIDS. We were 30. That sent me on another bigger grief spiral that again no one detected, or at least reached out about. I took a job at my alma mater largely based on that grief, and by 2018, I started to crack. I began counseling on March 7 – the anniversary of the day my friends and I saw Jeff in the hospital before he died two days later.

That summer was full of outbursts and manic episodes, leading into a fall with much of the same but during which I began seeing a psychiatrist and taking new medications. I had fights with my family members. I had hysterical phone calls to home. I sobbed as one friend held me on my couch. I texted my two best friends one night because I couldn’t stop crying, and the first one to get to me talked me down and made me laugh. My counselor asked if I had had suicidal ideation, and for the most part, the answer was no – nothing serious. But I had wondered what I was even doing with life, and what the point of it was.

That December, things exploded further one day during a talk with my boss in his office. I was mouthing off about something, and he lost his patience, letting me know that multiple coworkers had been in his office during the past six months, complaining about my behavior. My first reaction was defensiveness, and anger that no one had come to me about it, and then that turned to despair – a constant feeling of being misunderstood and perhaps even a failure finally confirmed.

“Does it even matter that I’m fucking depressed?!,” I cried out – Can I ever catch a break? – and then I began sobbing.

And my boss did something I’ll never forget. He got up, opened his door, and told his administrative assistant he was going to miss his next meeting. Then he came back and sat down, reached across his desk, and took my hand. He held it as I cried and told him what I’d been going through the past year. He periodically handed my tissues, and he talked with me about how he could have been better about letting me know when my antics were causing problems instead of letting them build up into one large one. He knew I was seeking help and hadn’t wanted to derail me. He believed in me, and he wanted me to get better.

If he had fired me, I probably would have deserved it. (I recall one particular profanity-laden outburst of mine that had several coworkers’ eyes as wide as saucers.) But he knew me. He knew I was more than my depression, more than my bad behavior, more than my fears and whatever demons were lying to me.

So, he gave me a chance to keep going, to keep trying.

I received additional medication, including an anti-psychotic mood stabilizer. I weened off it one terrible weekend several months later, and I continued counseling. By April 2019, my behavior was already considerably changed, and my boss and I smiled as we discussed my improvement one meeting, grateful for what we’d been through, what we’d learned, and how we’d trusted each other.

I thanked him for believing in me. He probably said “You’re welcome,” but what his actions ultimately said was that I was worthy of more than another chance – I was worthy of redemption.

That’s all anyone is looking for, and that’s the narrative and most works of art: Do I deserve it? Will I get it? Do I even want it? What does it look like? It’s the Bishop Myriel in Les Misérables, telling Jean Valjean to take the silver candlesticks in addition to the silverware he’d stolen. It’s the ghosts of A Christmas Carol, showing Ebenezer Scrooge that change was possible, even for him. It’s the entire plot of Mad Men!

It’s not a Get Out Of Jail Free card for all bad behavior. But it is a way to express good faith – to stop and see each other as inherently flawed yet inherently worthy of what is good, if we’re only given the opportunity.

The reason I’ve been able to manage 2019 and 2020 was because I got help, and coincidentally or not, depending on what you beleive, at just the right time. May 2019 saw my mother diagnosed with stage IV cancer. I moved home that November, while she was still feeling OK, and was able to adjust to my new life. By the time COVID-19 hit and I had to take care of errands, etc., soon followed by Mom’s ultimate decline and eventual hospice care, I was ready. But I didn’t get to that place on my own.

Jimmy Stewart, sadly, didn’t have to imagine the trauma George felt, having used his own experiences with depression, or at least PTSD, from his time in World War II to develop the character. In the scene in which George prays to God, his emotions apparently were all Jimmy’s as he said the line, “I'm not a praying man but if you’re up there and you can hear me, show me the way.”

George Bailey wasn’t scripted to cry, but Jimmy Stewart did.

“As I said those words, I felt the loneliness, the hopelessness of people who had nowhere to turn, and my eyes filled with tears. I broke down sobbing,” Stewart said in an interview in 1987.

I’ve been in that seat, wondering just what George, and Jimmy, thought. I’ve had Clarences help me, although with bi-weekly sessions and medications. And above all, I have been blessed by Marys in my life, not just my boss but family and friends who showed me grace (and a lot of patience) when I needed it most. That kind of grace transforms a person. When George is declared “the richest man in town,” it’s true – he is rich with love and with people who will show up for him.

They knew him, but imagine a world in which people showed up like that for complete strangers? I’m not talking about making donations or sharing a positive thought on social media. I mean seeing someone have a full-on breakdown in the store, and instead of taking out your phone to film them, try to get to them to ask what’s wrong and see if you can help.

This year has seen so many people in that seat, with so many also behaving badly, or selfishly, with most of it stemming from a deep fear that they aren’t in control of their lives like they had imagined. I try to remember that fear, and I try to extend grace toward those lashing out. (Well, toward most of those outside of Washington, D.C., anyway.) I try to see them through Mary’s eyes and take each case on good faith, whether I know the person or not.

My regular form is George. But oh, I try my best to be Mary – Mary, with her amazing grace.

How sweet the sound.

Really needed to read this after managing my husband's PTSD episode for the last 24 hours. His outbursts are getting easier to identify and anticipate, but it's still exhausting trying to navigate the manic chaos and I end up feeling guilty that I didn't do enough to ease the frustration he feels being the one going through it. I hope I'm a Mary but I still struggle to know how to help my George.

https://www.dilkhus.com/have-yourself-a-merry-little-christmas-lyrics/