Our house has never been completely quiet. Mom saw to that, tuning the living stereo to the local classical channel for as long as I can remember. She eventually had a radio in her room, too, playing the station – 88.3 FM – so that I could hear it in my room across the hall.

Around 5 p.m. Tuesday, September 15, 2020, the station played a track from a movie score, as it sometimes does. Mom was lying in her hospital bed in her room as I changed her ostomy bag (which she had named Burt). She’d had Burt for a year and stubbornly, determinedly changed him herself for most of that time, until her body wouldn’t let her stand long enough to do it. Then we changed it together, and toward the end, I took over. I was cleaning her stoma and powdering the surrounding skin when I recognized the tune, like a good Millennial: “Flight to Neverland” by John Williams, from Steven Spielberg’s “Hook” (1991).

I started thinking about Spielberg’s movie and his use of Peter Pan in several of his works. He often deals with the topic of abandonment, but in “Hook” he spends more time on the ideas of being a parent, family, what it means to grow up, and more importantly, the type of adults we choose to be. J.M. Barrie’s 1911 novel “Peter and Wendy” – adapted from his 1904 play “Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up” – sees Wendy immediately taking on a motherlike role for Peter after she asks “Boy, why are you crying?,” as Peter haplessly tried to reattach his shadow in her London nursery: “Not only had he no mother, but he had not the slightest desire to have one. He thought them very overrated persons. Wendy, however, felt at once that she was in the presence of a tragedy.” She played the role for her brothers, the Lost Boys, and even Captain Hook, Smee and the pirates. She felt needed – until she didn’t. Until she thought about her own mother, and she imagined her sitting in the nursery with its windows open, waiting for her children to return to her.

Once the Darling children do return home – and see that their mother, Mrs. Darling, indeed is sleeping in the nursery, waiting for them – they get into their respective beds to surprise her. When she wakes and sees them, she thinks she is dreaming. “The children waited for her cry of joy, but it did not come. She saw them, but she did not believe they were there.” Wendy, John and Michael run to her and convince her this scene she’s imagined so often is, in fact, real. “There could not have been a lovelier sight; but there was none to see it except a little boy who was staring in the window.”

I didn’t know my mother was dying when the music from “Hook” was playing. My brother Daniel and I, now going on little sleep and pure adrenaline, were in action mode, thinking she was having a bad spell somehow related to allergies and that she’d feel better soon. We thought she had a few weeks left. She had been up and visiting that morning, but now she couldn’t speak and was both hot and cold, and uncomfortable, and going in and out of sleep. It wasn’t until around 6:30 p.m., when we had a hospice nurse return to the house, that I realized I’d forgotten to give her one of her medications that morning: a steroid to help the pressure in her head, which contained cancerous tumors that had spread throughout a large part of her upper body from her colon. The last time I’d forgotten to give her the steroid was the day we began her hospice treatment (and for a time thought she was dying). We rationalized that she would bounce back once she got on track with her medication. The nurse gave us a few tips on how to keep her comfortable, and after she left, we decided to take a dinner break.

We ate, of all things, Taco Bell. It’s the weird things that stick with you, the absurd things. Like the fact that Dad, Daniel and I ate Taco Bell in the kitchen while Mom was dying in her bedroom. We just didn’t know.

I took a shower. Dad watched TV. Daniel called his wife, Tracy. Out of the shower, though, around 8 p.m., I could tell she was getting worse. I got Daniel, and we tried to suction out some of the mucus and saliva from her mouth like the nurse had shown us. Mom didn’t like it, and even bit down on my finger. I said, “She bit me!,” and you could see the tiniest hint of humor in her face. We realized later that she knew what was happening in the grander scheme and wanted us to stop.

For days, we’d had to help her in and out of chairs and the bed, and up and down off the portable toilet. Daniel would lift her while I’d move her legs, then pull her clothes and underwear down and back up. He’d get her back in bed while I cleaned out the toilet’s bucket. We knew we couldn’t move her now, not when she couldn’t help at all, so we decided to put her in an adult diaper. The comedy of errors that ensued was somehow sweet, as Daniel continued to use a soft and endearing tone with her that I can still hear, calling her Momma as he had been for months by then, a term I don’t think I’d heard him use since childhood. It took both of us lifting and maneuvering for me to get the diaper under her – only for one of the corners to rip. We managed to fix it somehow, as Daniel said, “It’s OK. Mom probably wasn’t perfect with these when she first started using them with us.” There was a slight smile on her face in response.

We kept monitoring her as she appeared to be burning up. We turned on fans and took off her nightgown, leaving her in a diaper and a sports bra. She started lifting her arms over her head, resting them against the bed, then down by her side, up and down. Her heart was racing and her breathing was labored. We watched her chest go up and down as she struggled. Once Dad came in to say goodnight, he took one look at her and knew things were bad. He sat in the seat of his rollator walker, in his pajamas, just watching her in silence. We decided to call the hospice nurse again. She arrived around 10:30 p.m. or so. I looked at Mom’s feet under her blanket and noticed they were getting darker; blood was pooling. The nurse then turned to me and said we had entered the end-of-life period, and that we needed to prepare ourselves.

I looked at the nurse, as we stood next to Mom’s bed, and said, “Jesus Christ.”

Miraculously, my father didn’t admonish me for swearing.

By the next day we were talking about how Mom must have felt the end was coming. Her sister came to visit that Monday, and her sister-in-law who was like a sister to her visited that Tuesday morning. That afternoon, Daniel put his wife on Facetime to say hi. And then of course the three of us were there with her. We realized she had made time to say goodbye without saying goodbye to the people closest to her.

It happened so quickly. The nurse stayed a while so she could watch Mom and answer questions we might have. We were all crying and took turns telling her goodbye, leaning over and whispering to her. She wasn’t responding like she had been before, but I believe she could hear us and understand. I told her I loved her and I promised that I would take care of Dad. The end-of-life stage can last for hours or days, so we decided to take shifts for the night. Dad and I went to sleep while Daniel stayed up. She was on oxygen, and the nurse had been given permission to give her additional doses of morphine and lorazepam to try and calm her.

Dad told me later that he prayed for God “to take her, to ease her suffering,” and he believes He did.

I set my alarm for 2 a.m. Daniel woke me at 12:30 a.m. to let me know her breathing had finally settled and she seemed more relaxed. I said “OK” and that I was going to go back to sleep until 2 as planned, and that’s a decision I’ve wondered about now for a year. Did I somehow know I was protecting myself? Was I even thinking clearly? In doing so, I feel I abandoned my brother, who sat vigil with her, talking to her in the early hours of the morning, until my alarm went off.

Once I walked in the room and looked at her, I knew. Daniel, still running on adrenaline, told me that her breathing was controlled, and that he’d put his hand to her mouth and felt her breath. I said something along the lines of, “I don’t think she’s breathing.” What he had felt was the oxygen machine, which we then turned off. I sat on the end of the twin bed and felt for a pulse. We both just stared at her, then looked at each other. We were 38 and 36, but we might as well have been 8 and 6 for all we knew what to do. Because that was our Momma, and she didn’t seem to be alive.

“Is this it?,” one of us asked, I can’t remember who. “Is this how it happens?” “I don’t know. I think so.” I reached up and did my best to close her eyelids, an action I’d seen in movies and on TV. Daniel went to wake up Dad and tell him. This really was a mercy; she passed without us seeing the moment it happened. She just slipped away.

I think I’m the one who called the hospice on-call nurse, Gilbert, who happened to be the one who did Mom’s hospice intake. The three of us sat in Mom’s room and waited for Gilbert to arrive. He was very kind. He talked us through what was going to happen, and then he called the medical examiner and the funeral home. We were lucky; all the hospice nurses were kind, and I have such a newfound respect for the profession that it’s hard to put into words. But there’s something sacred about a stranger who comes to your house and lovingly cares for your mother as if she were their own. Gilbert said as much about his job, that it was an honor to attend to her and show her respect. He prayed over her, and then the three of us moved to the living room while he cleaned and prepared her body for the funeral home attendants. He called her time of death at around 3 a.m. September 16, 2020.

The funeral home attendants were also nice, showing up around maybe 4 a.m. in business suits and doctor’s coats. Because I was her official caretaker through hospice – the one who handled the paperwork, the medications, all the calls and appointments, etc. – they addressed me as next of kin. (Dad was like, Um, excuse me?) But they explained more things and then went back to get her body. We didn’t watch her being taken from the house, and we didn’t view her body at all. We just couldn’t.

Daniel eventually went to sleep. I stayed awake and started calling family around 6 or 6:30 a.m. My aunt (Dad’s sister) and Mom’s brother both answered, immediately knowing. It took a few hours to reach Mom’s sister, which I did after a short nap. Daniel and I both wrote Facebook posts that we posted at the same time. That Wednesday was filled with meeting with the funeral home and fielding lots of condolences. I admit I still haven’t read any of the comments on my post. Maybe I will someday.

My breakdown came that night, when I had to call my two best friends because I was spiraling, having trouble breathing as I cried. I understand what gut-wrenching means now. What it feels like to be torn in two.

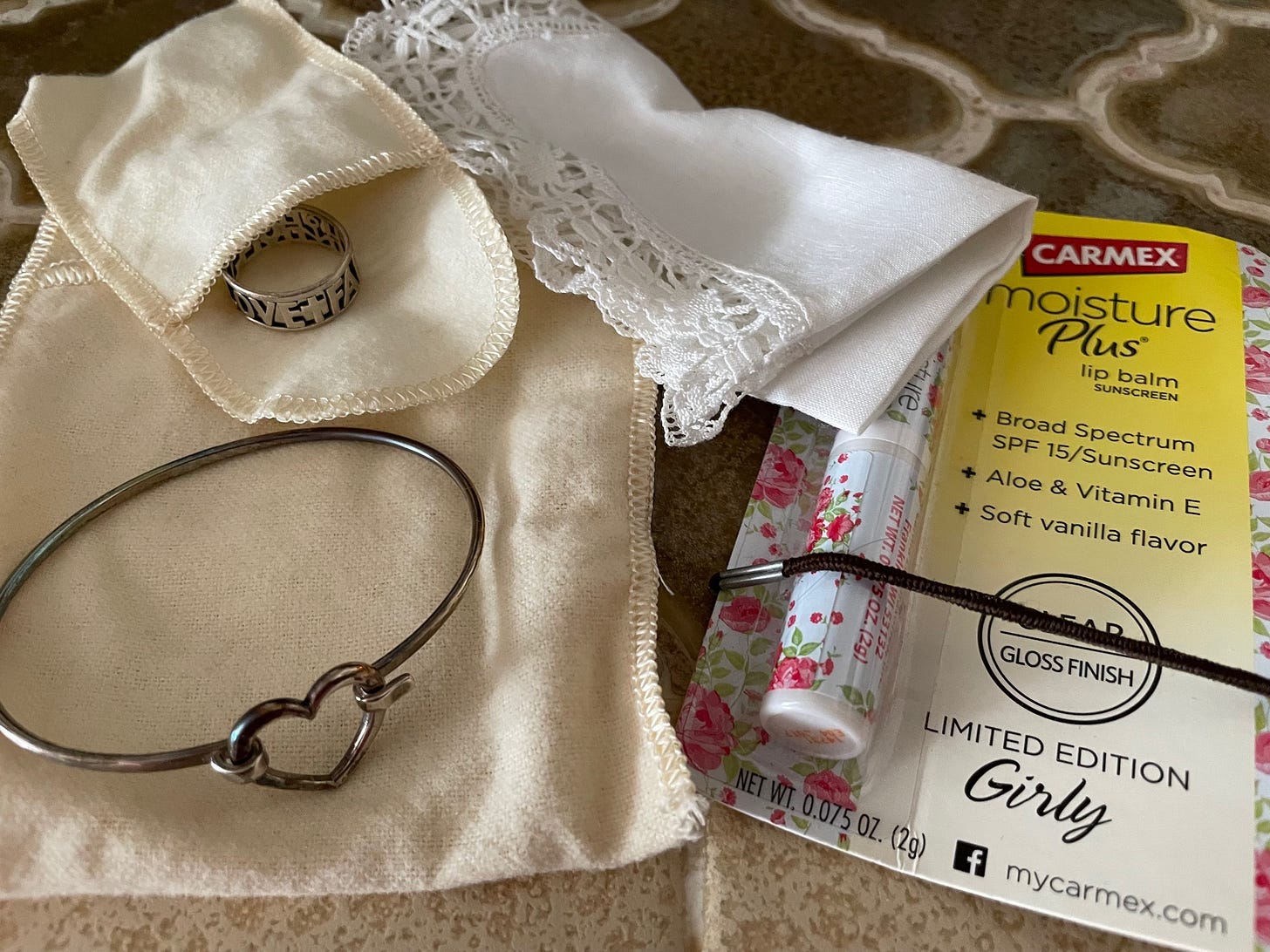

On Thursday, Daniel had to head back to Houston before turning around to come back for the funeral. My cousin Emily came to town to help me clean Mom’s room and dismantle the hospice furniture supplies. I also went around collecting what Mom had said she wanted to wear, including which jewelry pieces and which items she wanted in her pockets. (A handkerchief, lip balm, and a peppermint. I can’t tell you how many tubes of Carmex I sent through the wash because I didn’t know she’d left them in the pocket of her housedress.) I subbed a cough drop for the peppermint, but I couldn’t find one of the rings she requested.

Emily and I scoured her room but came up empty, and this also was one of the hardest times I cried. It felt like a type of failure, not being able to fulfill this simple request. It was one of many times I thought about how I possibly failed my mother. I’ve wondered if I sped up her death by forgetting that crucial steroid. “I let my mother die in a sports bra and adult diaper!,” I once exclaimed to my therapist, who has since been talking to me about the need to extend myself grace. Emily, bless her, was the level head – and grace – I needed in that moment.

We couldn’t have her funeral until the next Tuesday because the funeral home was back up thanks to Covid. The pandemic forced us outdoors as well, so we buried Mom in the rain in the cemetery where her parents are buried. When I arrived, the tent didn’t cover her casket all the way, so rain was dripping on it. Daniel immediately came to me, put his arm around me and said, “It’s OK. She’s OK.” Daniel and I both spoke, and Dad read the lyrics to a song.

Then we came home, and things were like they have been for most of the past year: just Dad and me. The pandemic, pre-vaccine, kept well-wishers away physically. No one really brought casseroles or came over to visit or help out with household chores. It was just … a year of me, Mom and Dad, and a lot of work trying to keep Mom alive, and then the dynamic changed forever.

I moved home in November 2019 not only to care for Mom, but with the long-term plans of caring for Dad. That was the reason she’d retired early, thus not having insurance when her cancer diagnosis came. His disabilities and make him a fall risk, and his essential tremors keep him from being able to do many things around the house. He can’t live alone.

My moving back to San Antonio wasn’t really a choice. It wasn’t an option to not take care of my parents, and I was in the best position to do so. I think this is one of the reasons I’ve held on to so much anger in the past year, however. I asked to keep my job but was told my position couldn’t be remote long-term. Management had every right to decide that, but it still has always felt unfair, as if my decision to move was capricious.

I officially learned on Sept. 9, 2020, that my final day was to be Oct. 30.

Mom stopped walking the next day. It seemed like it was one of the things she was waiting to learn, and once she did – even though it wasn’t the outcome any of us wanted – she began to move on. I’ve spent a lot of the last year trying trying to untangle the grief I feel for my mother with the grief of losing my job.

Dad and I watch a lot of movies, and a lot of HGTV. I handle his medication, and take him to his various doctor appointments. I take care of the family dog, Toby. I run the house. I’ve been on unemployment and I’m looking for work. I’ve been mostly inside for almost two years now, having spent the first winter working remotely and growing accustomed to being back home, not knowing a pandemic would make my homebody ways permanent. I live in fear of catching Covid and giving it to Dad. So, it’s us, and the occasional visit from family.

We’ve mostly found a rhythm. My schedule revolves around his meals and medication times. We’re working on getting him to a better place health-wise. I go with him to every doctor’s appointment and do a lot of the talking and listening and taking notes. I hear myself reacting to him in ways that she used to. I even sit in what was her chair and am more than a little bemused at where life has led me.

I have to fill a large role that she played, and in some ways, I feel like I’m playing a role. I’m not replacing her, but I have to fill her shoes a lot of the time.

The night before a risky surgery on Mom’s colon in August 2019, I started crying in her hospital room, saying that I was sorry she never got to see me get married and have children, things she really wanted for me. I can always say that I shouldn’t count out all of these life events for myself, but I can count them out as events she’ll get to see. She said I shouldn’t think like that, and that she was proud of me. But I still think about why that need to apologize was there.

A lot of the choices I’ve made in terms of where to live and where to work have contributed to where I’m at now, at 37. But then again, by not having a family of my own, I was able to move back.

This summer, I was looking through the drawers in Mom’s vanity for something. I haven’t cleaned them out; a lot of the things that were in her room were shoved into her walk-in closet and have yet to be sorted through. Her glasses are still where I put them a year ago. But searching that day, I found a bundle I didn’t know existed. Or if I had known, I had forgotten about it.

Mom had put together everything that was supposed to go in her pockets when she was buried, as well as that ring, a retired James Avery piece that was mine as a young girl, the words Faith, Hope and Love in block letters around the band. That ring that caused so much stress and tears last year, now practically winking at me. It was right where Emily and I had looked, but we hadn’t seen it.

The bundle has been on my bedside table since then. I haven’t taken it apart or worn the ring. I admit to wearing her engagement ring on my right hand a few times, as a way of having her with me. I’ve worn some of her clothes, too. The trinkets, of course, aren’t necessary. She’s a part of me like no one else is. She did her best to prepare me for the end.

In 2001, on the first anniversary of the day my best friend died in a car crash when we were 16, I wrote a short column for our church’s bulletin. I said that my childhood had died a year ago that day, and that still rings true. I feel, though, that our childhood – our innocence – dies multiple times throughout our lives. It’s the Romantic in me, I suppose.

Peter Pan doesn’t grow up because he refuses to make the choice to grow up – to see people as people, and to put others first and love unconditionally. He stays a boy visiting Wendy, then her daughter, then her granddaughter, with the cycle continuing as he is “gay and innocent and heartless.” He’s still on the outside looking in, or in the case of Hook’s Peter, who does grow up, a stunted adult going through the motions without realizing that our relationships and our families – the ones we’re born with or the ones we make – are all that ultimately matter.

“Finding Neverland’s” (2004) take on the origin of Peter Pan, which was in part inspired by Barrie’s relationship to the widowed Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and her four young sons, feels more optimistic to me in the face of the existential questions Barrie raised. Growing up doesn’t mean you stop believing, or that you have to lose your ability to have childlike wonder at times; it means you choose to keep believing despite all evidence to the contrary. It means you’ll do anything to try to save someone, or at least ease their suffering.

Several friends who had lost their mothers had told me in separate conversations that taking care of a dying parent is a holy thing, and they were right. It’s the best way I could honor her, and it’s why I don’t regret many actions that have led me here. I came back to continue growing up.

I came home, Mom. I’m home.